SYSTEMS OF FILTH

Priyanshu K

“What time is it?” she asked.

“It’s 1 p.m., sister,” I said.

“I have to do something for half an hour more. We get yelled at if we finish our work and leave early,” she muttered and continued work.

That was cue for me to wait as the powrakarmika I had approached on the street went about keeping “Namma Bengaluru” clean.

Half an hour later, the powrakarmikas sat on the footpath of a posh residential colony, their regular gathering point. Though it was only my third time meeting this group of sanitation workers, they made me feel immediately comfortable. I was sitting next to Usha akka* who has been raising her voice for the rights of powrakarmikas over many years.

Suddenly, a man on a scooter came by and asked them to move from the footpath. He left and came back a couple of hours later at two in the afternoon. There was to be a photograph session. “Some officer is coming …” “Oh no, I think some minister is coming …” “It’s not time yet, maybe that’s why …” Among many guesses and confusion, Usha akka said, “It’s better we speak tomorrow, sorry about this,” and walked away.

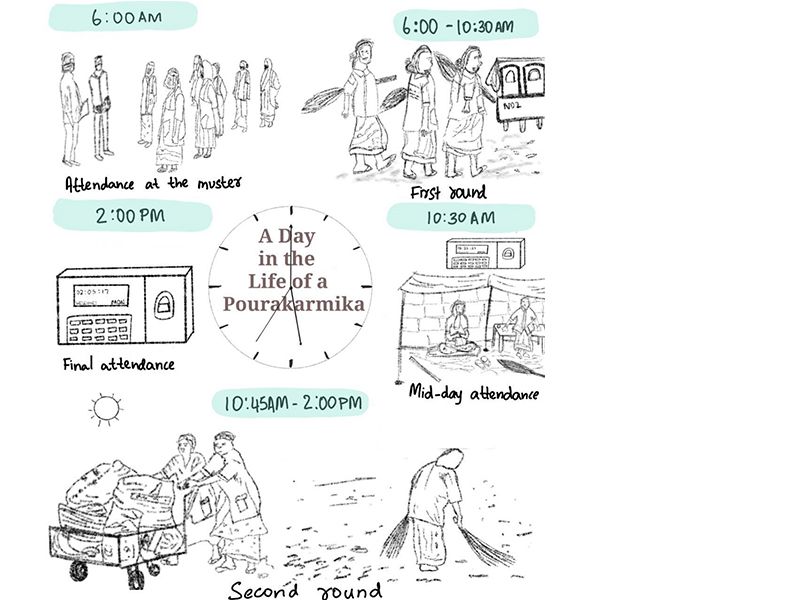

Usha akka called me around five in the evening: “We all left you alone and ran away, did you feel bad? Our inspector came on a round and we had reached there early, so he asked us to go back until it was time. He’s not always like that, today there was some big guy coming by that road.” She paused for a second, took a deep breath and continued, “For a long time, we fought for having biometrics, we thought that it would make our jobs permanent. It was of course for the better. We have uniforms, there is less torture by the contractors, our attendance and pay are not fully under his control anymore. But biometrics has also made our lives difficult. We have to walk three times a day to the muster to register our attendance. For some of us, it’s a long walk.”

Muster is the place where the sanitation workers gather to register their attendance. It’s supposed to be an office building, but it’s usually just a makeshift structure by the side of the road.

“Did you see my friend Chinnamma* who was sleeping on the footpath before the inspector came? We were all done with our work. She was very tired and felt sick. But she didn’t leave early as she had completed all her work and wanted to be there for the final attendance. Earlier, if we fell sick or if someone at home was sick, we could finish work early, inform the contractor and leave. However, with biometrics, we cannot leave early even if we finish our work.”

There is almost no flexibility at work for the powrakarmikas. Marshals and inspectors roam the streets on their bikes, keeping the workers under constant watch. To mark their attendance and claim their pay for the day, the workers have to show up at two, not before, not later. Even random passersby shout at them if they see them catching a breath, complaining about the streets not being clean.

“For a long time, we fought for having biometrics, we thought that it would make our jobs permanent. It was of course for the better. We have uniforms, there is less torture by the contractors, our attendance and pay are not fully under his control anymore. But biometrics has also made our lives difficult. We have to walk three times a day to the muster to register our attendance. For some of us, it’s a long walk.”

Illustration by Nanditha Ajith

Are mechanisms around efficient management through digital infrastructures merely to control the workforce and nothing more?

On our way, at every new lane, other powrakarmika friends of hers joined us. One was on her third day of period, another was recovering from an accident, yet another had lost a close friend to COVID-19. Although we chatted along the way, we maintained a swift pace of walking.

“Madam, you have to write about her,” said Meena akka, gesturing to a fellow worker. “She met with an accident while walking to the muster and had to miss work for weeks. She had a very difficult time at home. Her aged husband who drives an auto in the city had to take care of her. She didn’t receive any financial support. Leave that, there was a pay cut for all the days she missed!”

“Tell her about the dog bite,” whispered the friend Meena akka was talking about.

“Yes, so she finally came back to work recently and was bitten by a dog. She had to again spend so much time and money! Tell me, madam, did the accident and the dog bite happen when she was at home or at work sweeping the streets?”

“That’s why our union is demanding paid leave for health concerns.”

***

“After running around for three months and spending four to five thousand rupees, the officer who said the passport will be ready is now saying it won’t be possible, what should I do?” Lakshmamma* asked me over the phone. A leader of a powrakarmikas’ union in the city had earlier said that workers had to submit either their birth certificate, transfer certificate or passport in order to be part of the Employees’ Provident Fund plan.

“My family kept moving to different places until we finally started working as powrakarmikas in Bangalore. Nobody has a birth certificate and I never went to school, so that certificate isn’t there either. I had no choice but to apply for a passport. I spent a lot of time getting all the documents ready and going to these offices. Three months after we started the process, we had to leave the house we were staying at because we could not afford the rent anymore. So we moved to another part of the city. Now they’re saying my passport will not come because my address has changed.”

The union leader had said, “If we’d gone to school we wouldn’t be here sweeping, and if we could have passports, we wouldn’t be still struggling in this country. Just yesterday, a worker spoke about a power cut in their colony because she couldn’t pay rent on time. If her salary came on time, why wouldn’t she pay rent on time?”

***

The powrakarmikas’ work and their access to benefits is heavily governed by the ever-growing infrastructure systems, looming large over many who find it difficult to integrate within. These bold steps towards building ‘digital India’ have left many behind. If there’s a system in place to govern the work of the powrakarmikas, to ensure they do not take any extra break or leave work earlier, why are there still no rooms for them to change into and from their uniforms? Why are there no washrooms for the them to use in the middle of work? Why do they still have to run to a public toilet so many kilometres away from where they sweep? Why is there no system to record the injuries and deaths among them? Are mechanisms around efficient management through digital infrastructures merely to control the workforce and nothing more?

If residents and pedestrians have channels to file a complaint against the powrakarmika through the inspectors, why are there no formal channels for the workers to file complaints against the pedestrians or residents who are disrespectful, unnecessarily pass comments, question their work or use foul language? One cannot separate the caste identity from the workers’ conditions at work, a systemic oppression that has continued for centuries in different forms.

The stories shared here remind us that very often we are complicit in reinforcing the divide and deepening injustices in the name of technological progress and infrastructural development.

*Names have been changed on request

Priyanshu is working on a research project in the area of gender and labour and is a music and theatre enthusiast.