“OUR REGISTERS DON’T ASK FOR OTPs”: ANGANWADI WORKERS AND THE DIGITALISATION OF WELFARE DISTRIBUTION

Yameena Zaidi

“There are problems on top of problems,” Rukmani* said, reflecting on her experience of being an anganwadi worker in Delhi’s North-West district for over fourteen years. “We work more than as teachers but we get nothing. There’s no pension. Our honorarium is so less and that too only paid partially. Whether it is for Pension Yojana, Aadhaar-related work or COVID-19 surveys—they give all this work to us. Then they expect us to stay silent and accept it?”

These were some of the many issues that made women like Rukmani join the Delhi State Anganwadi Workers’ and Helpers’ Union, which has been at the forefront of demanding regularisation for the workers and helpers who are considered volunteer workers by the State. Regularisation would allow anganwadi workers to earn a salary like other government employees instead of the meagre honorariums that they are currently paid. In Delhi, as of 2021, workers were to be paid an honorarium of Rs 10,000, while helpers were supposed to get Rs 5,000. Even this meagre amount was withheld for close to a year in 2020–2021. To protest this, anganwadi workers and helpers from across Delhi had gathered at Rajghat in September 2021. Their demands ranged from the issue of regularisation and the partial payment of honorariums to the increase in workload due to the New Education Policy 2020 which expected anganwadi workers to contribute to primary schooling. This would have been in addition to their current responsibilities of conducting pre-school activities, distributing take-home rations, assisting in immunisation, visiting homes of pregnant mothers, conducting surveys on community health, etc.

Regularisation would allow anganwadi workers to earn a salary like other government employees instead of the meagre honorariums that they are currently paid.

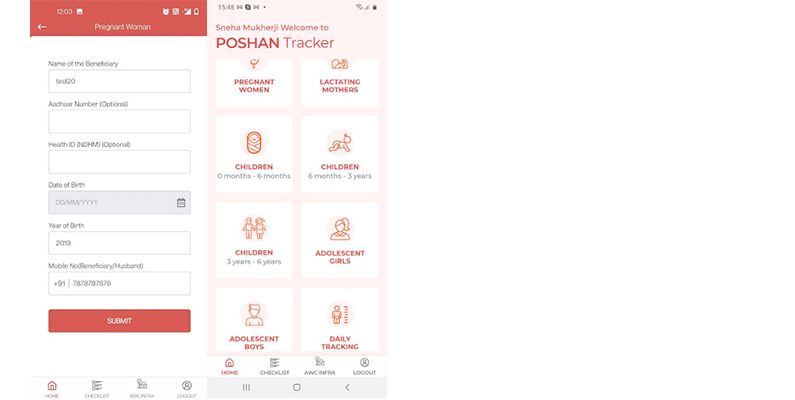

The workers were also protesting against the mandatory implementation of the Poshan Tracker app. Launched in January 2021, the app replaced the previously used Common Application Software (CAS). Anganwadi workers were to input the nutritional information of the beneficiaries—pregnant women and children—of the anganwadi they worked in. The new app was to be downloaded on the same phones distributed by the government when CAS had been rolled out in 2018.

“Delhi government has given all workers smartphones, but smartphones alone don’t do anything. The payment for sim card charges doesn’t come on time,” Rishali, a representative of the union, said. Anganwadi workers were promised a monthly amount of Rs 200 for the sim charges but workers claimed that even when the amount was paid by the government on time, it did not cover the actual monthly expenses incurred on the sim. “They gave us postpaid sims and the bills are very high. The amount is more than what the government has guaranteed us, even though the workers are only using the phones for official purposes,” Rishali added.

Poshan Tracker app only records information in English (Image Source: Google Play)

On facing problems with the app, the only official avenues for support available to the workers were also digital. They could either use the online helpdesks which allowed them to create a ticket or request for assistance through email, call or video conference. Most anganwadi workers said that they often turned to YouTube videos to seek guidance about app functionalities and updates.

Discussing the issues with the phones, Rukmani said, “Most of the phones keep hanging. Many of the workers have paid out of their pocket to get their phones repaired. Getting these faulty phones fixed has also become our responsibility.”

“The app should be shut down,” she said when asked about the mandatory implementation of the Poshan Tracker app. “They introduced the OTP system recently for the beneficiaries, and we have been facing problems since.”

As per an update released in September 2021, the app required the phone and Aadhaar numbers of all beneficiaries to be verified. In order to register new beneficiaries, the Anganwadi workers needed to input a one-time password (OTP) received on the beneficiary’s phone. “Many of our beneficiaries are mothers who don’t have phones. They have one phone at home which their husbands take with them or their children are using for online classes. They are ready to take welfare from anganwadis but to register these new beneficiaries we have to input the OTP. They have to give us the OTP within five minutes but there are all sorts of problems with internet and phone connections. Five minutes are not enough,” Rukmani said. While OTP is one of the major problems anganwadi workers and the beneficiaries faced, the issues were manifold and often systemic in reality

On facing problems with the app, the only official avenues for support available to the workers were also digital. They could either use the online helpdesks which allowed them to create a ticket or request for assistance through email, call or video conference. Most anganwadi workers said that they often turned to YouTube videos to seek guidance about app functionalities and updates.

Individual content creators post videos after every Poshan Tracker update. (Image Source: YouTube)

In contrast, older anganwadi workers like Rukmani and Savita* seemed to find a degree of familiar comfort in maintaining the registers. Their distrust of digitalisation efforts was clear. “We keep the register for our own convenience,” Rukmani said. “Things can get deleted on the app. Sometimes the app doesn’t work. But the information on the register remains. If they ask us for a record tomorrow, how will we provide it? All this information should be on the register. Anything can happen with these apps.”

The situation was worsened by the fact that details of beneficiaries could only be input on the app in English. “Many of us don’t know English that well. Some younger workers in Delhi are able to use the app, older workers like us have to struggle and manage on our own. First, they gave us the CAS app, now they have given us the Poshan Tracker app,” said Savita. “They give us one app, it doesn’t work, then they give us another.”

The technological scepticism is not just rooted in the fact that digitalisation creates difficulties for many workers but also in the appification of the Poshan Abhiyaan which seeks to improve the nutrition intake of women and children in India. Rukmani noted the irony in asking people who depend on the government’s welfare initiatives for phone numbers and OTPs: “Our beneficiaries don’t have food to eat. Why does the State expect them to have phones? Some have phones but they can’t read, so they don’t know how to access their messages. How will they give us an OTP?”

The digitalisation efforts of Poshan Abhiyaan—to remedy issues of malnutrition by “leveraging technology, a targeted approach and convergence”—is a prime example of a neoliberal State solving issues of public health by functioning as a mere centralised distributor of goods and services to beneficiaries. The Poshan Tracker app then becomes a digital platform through which the logistics of distribution are mediated, leaving anganwadi workers to become delivery agents rather than frontline community workers of social change.

*Names changed on request

Our beneficiaries don’t have food to eat. Why does the State expect them to have phones? Some have phones but they can’t read, so they don’t know how to access their messages. How will they give us an OTP?