ID NUMBER 817340

On her first day at work, standing in front of the tall gate and high walls, Radha took a deep breath and willed herself to stay calm. The city was home to several generations of her family, and she, like her mother and grandmother before her, had always worked in small neighbourhoods, in houses that didn’t have the ambition to grow beyond the first floor. But the lockdown had changed everything. Here, one … eight … twelve … she counted eighteen floors in all. She walked toward the gate, where, inside a glass cubicle, she could make out the silhouette of a lone man. She hovered by the barricade, until his voice shrieked on the intercom. “What?” She took a few steps closer, but he didn’t show any signs of lifting the barricade. She had been hired to work as a cook, she said softly. The barricade lifted halfway so she could squeeze past. “Fill your details here,” he said, flinging a register at her. “And your photo? Aadhar card?” She opened her purse and handed over the documents. She was prepared for this. Five or six years ago, she would have gone around the neighbourhood, met prospective employers, negotiated a rate, and begun work the next day. It was different now. Her profile had to be made, she would have to come back tomorrow. The next morning, when he saw her, he buzzed the intercom. “ID 817340.” The gate swung open.

***

It had been three months since her last job, and Sunita was running out of options. Her son’s school fee was due and she had already taken a loan from her family back home. Every morning her in-laws lectured her about giving up the house and moving back to their village in Bihar. It would certainly reduce costs. But in spite of the struggle and strain, Sunita liked the city. She didn’t want to return to the village, to till the land under the hot sun and take care of her in-laws. Here, in the city, she felt she had control over her husband, her son, her own life.

Her husband drove his auto from morning to night, but it still wasn’t enough. She had to find work.

“Why are you so late? I have work to get to. On the app Manju said you left her house at 10.10 a.m.”

That evening, as she made her way to the tanker to fill water in the pots, she saw a crowd of women near the local kirana store. Pushing her way closer, she saw a woman handing out cards. “If you want a job, come to the office in Ulsoor with your Aadhar and photograph.” She took the card home and asked her son to read it out for her. “It says if you sign up, they will find you work.” The next day she reported to the office at 10.00 a.m. At noon, after two hours of standing under the sun, she handed over her documents. “We will call you,” said the man behind the desk, peering at his computer. Feeling hopeful, Sunita returned home. Her phone did not ring for the next week.

***

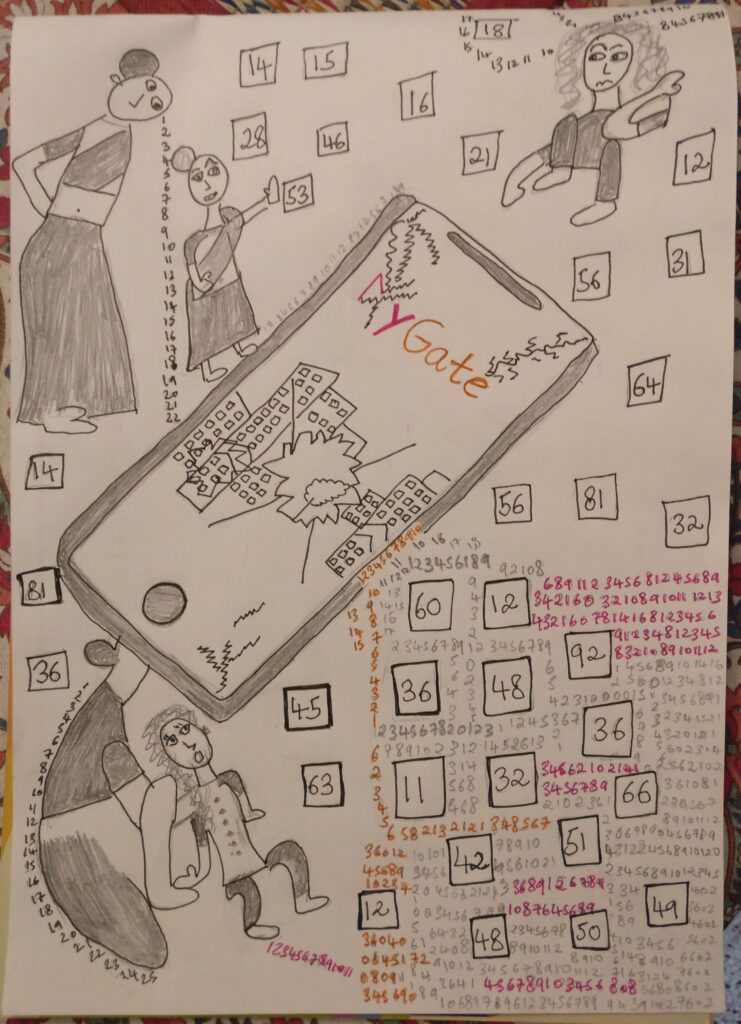

Illustration By Angarika G

Looking at Sunita, she asked, “Your caste?” On hearing the response, the woman turned to the other two workers. Sunita didn’t get the job.

“Why are you so late, the app shows that you entered the complex at 8.35 a.m.? Wasting time talking in the basement ah?” the madam said.

Ignoring the jibe, Radha started her work. Dosa for the children, poha for the husband, eggs for the madam. Then cleaning, dusting, washing clothes. It took an hour and a half, a little longer than expected. The lift still wasn’t working. Running down four floors, she knew what was coming: “Why are you so late? I have work to get to. On the app Manju said you left her house at 10.10 a.m.”

Her grandmother’s words came back to her: “When you’ve lost everything, turn your heart to stone.”

She ran up four floors, without stopping to check if the lift was working. “If you come late once more, I’ll have to let you go. Dust the house fast.” “Not with that broom, use the vacuum.” The madam disappeared into the kitchen and got on the phone. “They are a complete nuisance, never on time. Did you hear that the one working in Preeti’s house asked for a raise? For her daughter’s wedding. They think only they were affected by the lockdown.” Radha walked into the kitchen and intentionally turned on the vacuum. The machine drowned the woman’s voice. She smiled to herself.

Before the lockdown, she could have earned up to Rs 4,500 just for cooking. She didn’t have a choice.

“Come to the Domlur crossing tomorrow and call this number.”

“But that’s almost forty-five minutes away from my house.”

He hung up before she could ask anything more.

Arriving at the designated spot, she saw two other women, waiting just like her. An hour later, a man turned up on a scooter. “This way.” They had to follow him on foot for fifteen minutes. The house had a large gate and an ill-tempered dog tied to the gate. They waited for another twenty minutes. By this time, Sunita’s neatly oiled hair had come loose and her fresh jasmine flowers had shrivelled in the heat.

Finally, a woman emerged from the cool shade of the house. She looked at the three women. “What can you cook? What language do you speak?” Looking at Sunita, she asked, “Your caste?” On hearing the response, the woman turned to the other two workers. Sunita didn’t get the job.

“What about giving me the money I spent on the auto?” Sunita asked the man when it was all over.

“That’s the cost of finding a job,” he said and sped away on his scooter.

Sunita walked back home.

***

“Calm down and drink some tea!” said Sangeeta, carrying a small tray with paper cups filled to the brim. It was the monthly union meeting of domestic workers in the city. Looking around, Radha saw a few new faces.

“Tell us what happened,” Sangeeta said, pulling out her register.

“Madam gave me a new sari for Diwali.” Shobha had joined the union a year ago. “On my way out, the guard asked to check my bag. I didn’t want him to, I had my period. Was he going to check everything? He refused to listen, and right there on the table, in front of everyone, he pulled out everything. He found the sari. ‘Where did you get this from? Why hasn’t your madam filled it on the app?’ He made me walk back and ask her to enter the details.”

Pushpa joined in, laughing, “Even if she gives me twenty rupees to buy her milk, she enters it on the app. I prefer it this way. Otherwise they’ll accuse us of stealing!”

Turning to one of the new faces in the room, Sangeeta asked, “I’ve not seen you in a while. How are you?”

Usha had lost all four of her jobs during the pandemic. Her son had enlisted her on an online platform just a month ago. When Usha went to the agency’s office the next week, she noticed a cupboard full of files. Later she realised there was one file per worker, and the agency had over 5,000 files. After submitting her Aadhar card, photographs and voter ID, Usha’s profile was updated on the platform.

“All our details are made available”

Like what?

“Where we are from, the language we speak, what we can cook.”

Do they ask about caste?

“Yes, at the time of registration. And the employer asks about cooking—Brahmin style, Gowda style, etc.”

At least when she wore the ID card she wasn’t asked any questions by the other residents: “Who are you?” “Where are you going?” “I haven’t seen you here before.” She had paid for her peace of mind.

Do you know who you’re going to work for?

“No. There are no details about the employers. So, we never know where we’re going to get called for a job.”

How much do you get paid? Cooking, cleaning?

“The agency fixes the rate. But usually for one hour, it is Rs 250. Here, everything runs based on time, not work! And you can’t negotiate. Everything is decided by the app.”

Can you choose which jobs you want to do?

“Cooking, cleaning is usually assigned to women. But men get the big cleaning jobs.”

Do you get the full amount?

“No, the agency takes a commission. We don’t know how much the agency takes.”

Haven’t you asked?

“They just give a phone number. You have to keep calling it every day, an automated voice will tell you that your call is being forwarded. But no one ever calls back.”

“Why didn’t you come for the last meeting?” asked Sangeeta, concluding the chat about the agency.

“We are not supposed to join a union. It is mentioned in our contract. I was afraid. I don’t want to lose my job,” said Usha.

The meeting gradually drew to a close. A few women stayed back to discuss problems they were facing in accessing the government compensation promised to domestic workers. Others hurried home to cook dinner, tidy the house and prepare for the next day. Rushing to catch up with Usha as she was leaving the meeting, Radha asked her, “Do you like working like this?”

“I don’t have a choice. My husband is very unwell. It helps that I can choose when I want to work and where I want to work. But I also feel lonely. There’s no one to talk to, I can’t ask for leave, for a bonus,” Usha said, shrugging. “You know, 50 per cent of Bangalore runs on this,” she said, smiling and waving her smartphone. “Now, so does my life!”

***

“How did you get my number?” Sunita asked the employer as she finished drying her clothes.

“On this platform,” the madam said, holding out her phone.

Sunita took a closer look. There was her photograph, her marital status, caste, language, cuisines she could cook. It was all the details she had given the placement agency, but they had never mentioned putting it online. It was only supposed to be through phone calls.

“Didn’t you sign up for this?” her employer asked.

“No.”

Sunita walked home with a strange sensation in her stomach. Where else was her picture being used?

***

Nearing the gate, Radha took her ID card out of the bag and slung it around her neck. According to the apartment policy, the employers were supposed to get cards for workers. But Radha had to spend Rs 500 and get it done herself. It had been a year since she had begun working in this complex. At least when she wore the ID card she wasn’t asked any questions by the other residents: “Who are you?” “Where are you going?” “I haven’t seen you here before.” She had paid for her peace of mind.

At the barricade, the security guard updated her arrival on the app. In his hand, she could see her face flash up on the phone. She hadn’t had the chance to see this app. She wondered what other details were on it. A few of the other workers had told her that the employers gave them ratings, like the Uber/Ola drivers, based on which they might get more work. There was also talk of a WhatsApp group where residents could discuss the workers. Her friend, Parijata, had lost her chance at a bonus because of this group. She had asked for a thousand rupees for her daughter’s wedding. The employer put it on the app as a complaint. After that, none of the other employers entertained her request.

Thousand rupees, she thought later, clearing the owner’s dustbin, filled with packages and plastic. That’s how much they probably spent in a few hours.

“Here, take this, it might fit you,” the woman said, handing her a plastic bag.

Radha looked inside. They were old clothes, faded and torn. The woman entered the details on the app. At the gate, the security guard emptied the content of her bags on the table. He checked the plastic bag. She repacked it and waited for the barricade to swing shut. Turning left, she threw the bag into a dustbin. It was a long walk back home.

*This article is based on interviews and conversations with local and migrant domestic workers in the city. A special thank you to Stree Jagruti Samiti for their valuable input, Ravi Ranjan for his research and translation and Priyanshu for research assistance.

Angarika works at Maraa, a media and arts collective, as researcher, facilitator and practitioner.