PRESENT CONTINUOUS

Angarika G

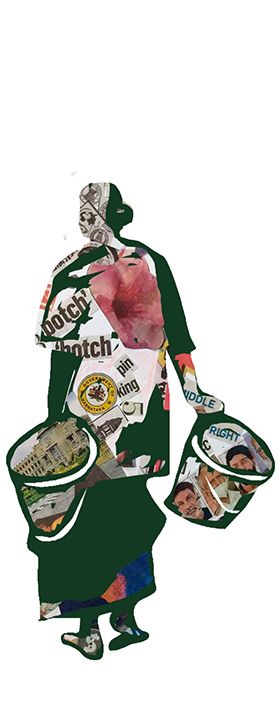

In conversation with powrakamikas, domestic, sex, garment and migrant workers, we tried to represent stories of violence, untouchability, exploitation, and injustice as descriptions or questions to the middle and upper class/castes in angry, melancholic and sarcastic tones. We also spent time with workers in their homes, and in their brief moments of leisure, where we learnt of fantasies which escape the mechanization of daily life. Our conversations began to unfold the inherent contradictions within capitalism; degrees of alienation produced by work ; frictions between individual struggles and processes of collectivization; conditions and structures that produce exploitation and discriminatory practices; the body and its relationship to labor. The experiences of the women workforce foregrounded the connections between home, workspace, and public space, as she negotiates her time between freedom, responsibilities, and aspirations.

What ‘voice’ do we use to situate an experience?

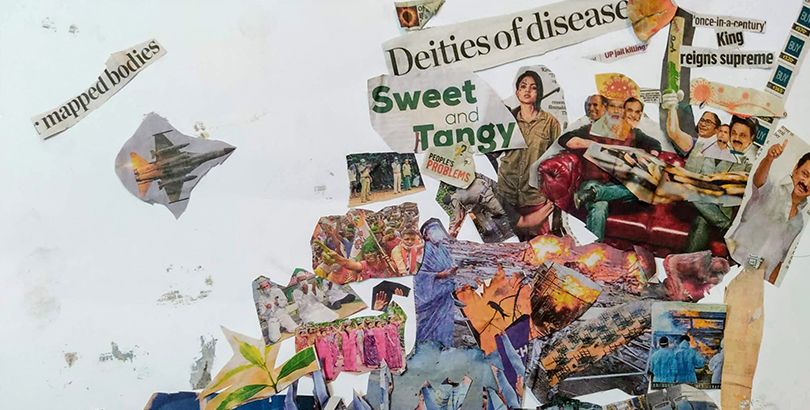

Questions of inter-dependence and exploitation between various publics in the city came into sharp focus during the Covid 19 crisis. The media was full of images which depicted workers as hapless victims. Further, in most coverage, civil society activists, academics, government representatives were called upon to speak for workers. We were keen to challenge this representation. We launched a Youtube channel, where we encouraged workers from our networks to produce videos/images about their experiences. A move toward self-representation, where workers could share their experiences without the framings and assumptions of upper-caste/class publics. We did not want to assume the crisis in a worker’s life, nor their demands or desires. Further, our intention was to start a conversation between diverse groups of workers, a space for collectivization, free expression, discussion, friendship and solidarity.

We faced many challenges. For example, we were not able to figure out a smooth process for content distribution. Due to a lack of time, workers were unable to produce content regularly. The women lacked frequent access to smartphones to be able to shoot and record, and so on. However, the channel is still active. Moving forward, we hope to organize media trainings, specifically for the women workforce and their children. We will continue our efforts to encourage various networks of workers to produce content that can speak in a manner of their own choice, on their own terms.

In the meantime, we continued our practice of writing about labour and our relationships with workers. In March 2021, a year after the first Covid 19 lockdown, we planned for a ‘retrospective’ issue of Bevaru. But with April, came the news of another lockdown. This time there was a strange sense of preparedness and resignation. One of the construction workers we met last year, called us before the lockdown was officially announced and said he was heading home. “I’d rather stay hungry in my village than suffer the humiliation of last year again.” But no one was prepared for the loss of life that followed.

Alongside many others, we set about raising funds, ensuring ration and wages, trying to help workers access basic healthcare. Confronted with the grim realities of the new lockdown, we wondered what to write about in the next issue of Bevaru. Should we stay true to the experiences of the last year? How do we write about death? Oscillating between lockdown and unlocks, how can we read into the past to make sense of the present and what are the visions for the future? Should the tone be reactive or reflective? Or should we just remain quiet and mourn the loss of life around us?

The question, however, was not only about what to write, but also how to write. We set ourselves the task of writing ourselves into our pieces, to reflect on our relationships with workers. We tried to move away from observing and reporting facts, and dwelled more on our own caste positions, within the chaos and grief around us. Challenging our own representations from previous issues, we did not want to escape the frame.

We grew conscious of the ways in which we consciously and unconsciously reveal ourselves. For example, what ‘voice’ do we use to situate an experience? Passive or Active? What does it reveal about our position within an interaction? How honestly can we receive what another person says or does, and how much gets colored by our own projections? Why should a workers’ story provoke only guilt? What else can it provoke? What images of workers are showcased to evoke empathy amidst a violent and cruel hierarchy of power? Situated at opposite ends of the class-caste spectrum from worker, how do we acknowledge this difference within our writing?

We wrote about our experiences with workers we have spent deep time with, not limited to the ‘crisis’ of the virus alone. Disagreements that underlie our differences and confessions that brought us closer together. As a worker shared, “When someone asks how you are, you feel you are not alone in your sorrows. You share a little and in that moment, you feel a little lighter.” We chose to illustrate our own pieces, with drawings/paintings/posters that perhaps capture a mood, a fantasy, an observation that escapes the confine of our words. We chose not to translate each piece to retain the ways in which language shapes our perceptions.

From one lockdown to the next, we have been forced to reckon with the circularity of our utopias, casting light on the failures of political and social imagination and accountability. There are many questions and conditions to reckon with. As we move forward, we hope to transition Bevaru into a quarterly magazine. This issue is a step in that direction, with explorations that are not definitive or prescriptive. We lay bare our struggles in absorbing, witnessing, and representing the violence and grief around us. We hope we have done justice to the resilience of our friends, and the dignity of their assertions.